We must move to survive. Yet each movement we make — from acquiring food, to eating, to caring for our children, to protecting ourselves — requires our brain to make hundreds of adjustments and adaptations based on past experiences and the present environment.

Little is known about how neurons in the motor cortex — the part of the brain that directs skilled movement — process and apply past experience to coordinate skilled movement. But new research from the Technion has given medicine insight into what happens in the primary motor cortex (M1) when learning skilled movement, which may lead to the development of new treatments for brain diseases.

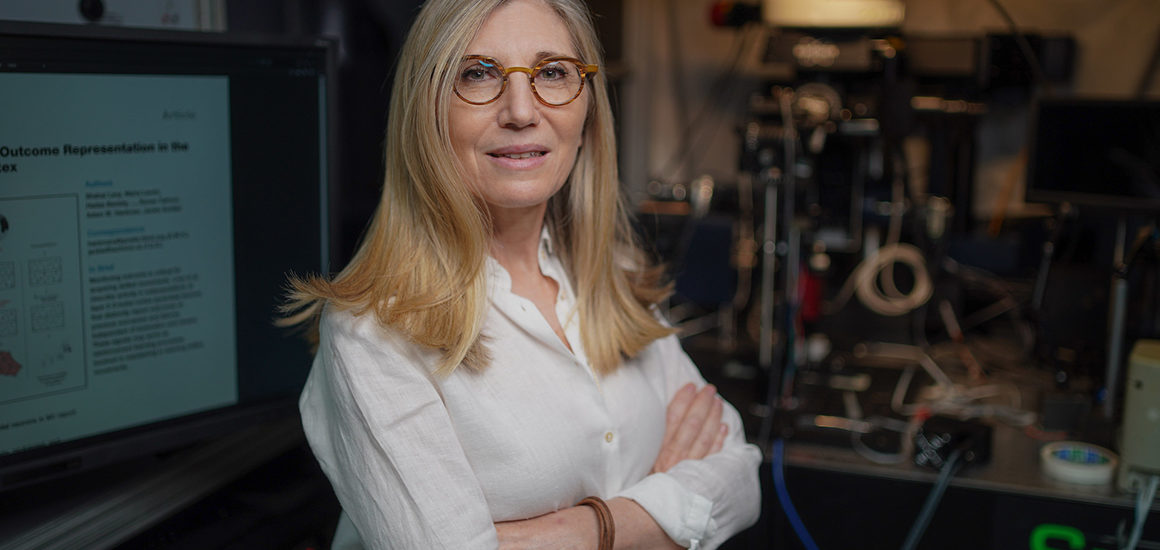

The research, led by Professors Jackie Schiller and Omri Barak of the Technion Rappaport Faculty of Medicine and lead students Shahar Levy and Maria Lavzin, together with Professors Ronen Talmon and Ron Meir and postdoc Hadas Benisty from the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Faculty of Electrical Engineering at the Technion, employed biological and computational methods that included imaging, genetic, behavioral, and advanced computational tools.

After observing the M1 of mice reaching and grasping for food, the team discovered two different neuron populations report successful or failed behavior attempts back to the brain. This indicates the brain takes a global assessment of motor performance, rather than looking for a specific parameter or reward to assess performance. Researchers also discovered that neurons “remember” the outcome (in this case, whether the mouse successfully received food) for the next trial.

According to Prof. Schiller, the brain’s use of performance outcomes may be a key reason why the M1 is essential for skilled, dexterous behaviors. The researchers also observed that outcome evaluation is carried out by different neurons than movement generation. They suspect this separation may be beneficial in some yet-unknown way.

The new research could be a key to improving movement in patients, such as those suffering from Parkinson’s disease.